Bodikon (ボディコン), or also referred to as Otachidai Gyaru (お立ち台ギャル) is a style and subculture that was centered around the distinctive style of dress by the same name, the bodycon, (of which its name is a shortening of the pronunciation of the English words "body conscious"), but was not entirely based around the dress, and would come to include the general female fashion of the Japanese Bubble Economy period.

Bodikon is the direct predecessor of Gyaru, and virtually all Gal styles. The first “Gals” were Bodikon women, and the emergence of the first styles of Gyaru around 1993-1994 came largely from the “radicalisation” (described later on this page) of Bodikon style. Bodikon is therefore classified as “Gal”, and can be considered a part of the larger Ametora umbrella (which includes styles like Amekaji), though it does not typically emulate 1980s and early 1990s American fashion trends.

This style was most popular in the mid-to-late 1980s and early 1990s (usually around the period from late 1985 to 1994 at the peak of its popularity). The style was influenced by the Japanese economy at this time, as well as the widespread popularity of dance-based nightlife in Japan in the 1980s and 1990s (especially venues playing Italo Disco, City Pop, Eurobeat, Hyper Techno/TechPara, and House music). There are also parallels with the mid-1980s Japanese trend of the satirisation and exaggeration of American fashion and lifestyles.

History[]

NOTE: The history described here is long and highly detailed.

The body-conscious fashion presented by Tunisian couturier Azzedine Alaïa at the 1981 Milan Collection was the first of many experimental dress designs throughout the earlier part of the 1980s to attract attention internationally. By the mid-1980s (especially from the autumn of 1985 onwards following the signing of the Plaza Accord), Japan was reaching its economic peak in what became known as the “Bubble Economy” (Baburu Keiki/Baburu Wa, バブル景気/バブルは). The Bubble Economy was a very large economic bubble in Japan focused on asset prices, land prices and the Nikkei 225 stock exchange. It made Japan the 2nd largest economy in the world (after the United States) and the world’s largest creditor nation by 1988. It was caused by the Japanese yen rapidly (and artificially) strengthening against the US Dollar after the signing of the Plaza Accord in September of 1985. In response, the Central Bank of Japan slashed interest rates to 2.5% and held them there, making them the lowest interest rates in the world and also making credit available as never seen before in the history of Japan. In fact, the interest rates were so low that loans became practically free. Investors, suddenly with huge amounts of money to blow, plowed borrowed money into real estate and stock markets, shooting prices on a rapid upward streak, as well as borrowing against their newly appreciated holdings and buying even more. With both land prices and also salaries soaring in order to balance the real estate surge, by 1988 Japan’s total land value surpassed all of the land in the United States four times over. To highlight the extreme land prices, the total cash value of a single ward in downtown Tokyo (Chiyoda-ku) in 1988 could have purchased all of Canada- and the gardens of the Imperial Palace alone surpassed all of the land value in North America combined. Some of the most extreme land prices were found in Tokyo’s Ginza luxury shopping district- where land was sold for $250,000 (¥30,000,000 at the time) a square meter. The yen had become the world's powerhouse currency, and Japanese businesses also now found they held tremendous buying power overseas. It was widely feared in the West at the time that Japan would overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy. Japanese corporations, encouraged by the strong yen, began to develop a strong domestic economy in Japan - while also maintaining high exports of technology and cars to the United States. These Japanese corporations were now outperforming American ones. Now, nine of the world’s top ten banks were Japanese - with Tokyo banks the world’s biggest and most powerful. By early 1989, by market cap, Japan accounted for 45% of the global stock market, far more than the US’ share of 33%, and eight Japanese corporations, five of them banks, were in the top 10 largest companies in the world, ranked by market cap.

Encouraged by the booming economy, the Japanese public were encouraged by the government to spend - and they spent both massively and decadently. $500 cups of morning coffee drank by housewives and sushi were reported to have been sprinkled with gold dust in Nara and Osaka, in the belief it brought good health. After the release of the 1987 romantic comedy film “Take Me Out to the Snowland” (私をスキーに連れてって), there was a “skiing boom”, and ski resorts were constructed in huge numbers and filled to the brink with customers, resulting in very long queues. Imported cars such as BMWs, Mercedes Benz cars, Ferraris, Porsches and Rolls-Royces, especially left-hand-drive models (as this implied you had the money to import a LHD car to a RHD society like Japan), surged in popularity. It even got to the point where many Japanese women wouldn’t date a man who didn’t drive an imported car, claiming their arms were “allergic to the seats of a Japanese car”. Businessmen entertained each other with easily $184,000 worth of partying in a single night and bought gold bars as investments. People flew from Tokyo all the way to Sapporo just to enjoy a bowl of noodles and famously waved ¥10,000 banknotes and three fingers in the air on a Saturday night to get taxis, as taxis were so scarce due to the numbers going out on the town. Japan became the largest consumer market of luxury goods and there was even imitation of foreign European cuisines such as Italian food at restaurants around the country, resulting in the birth of “Itameshi” (イタめし) cuisine. The Japanese also went on a huge buying spree abroad - encouraged by the opening of the new Narita Airport, the Bubble causing appreciation of the yen, and plans to double overseas travel from 5 to 10 million Japanese between 1987 to 1992 by the government. The Japanese purchased large investments such as “virtually every skyscraper in Los Angeles”, a quarter of California’s whole banking market, major American companies (such as the purchase of Columbia Pictures by Sony in September 1989) as well as large properties in places such as Hawaii, Australia, British Hong Kong, the US and all over Europe (particularly in the south of France). There was even large-scale purchase of European art, such as the famous $39,921,750 purchase of van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers at the Christie’s London auction-house by Japanese insurance magnate Yasuo Goto on March 30th, 1987. At the time this was a record-setting amount for a work of art. Another particularly famous investment was the purchase of the Rockefeller Center in New York by Mitsubishi Group in November 1989- raising fears of the Japanese buying up symbols of American capitalism. At the same time, Japanese tourists, often travelling in organised group-tours, were travelling abroad in increasingly large numbers - the number of Japanese people traveling abroad per year in 1986 (the 2nd year of the Bubble) was about 5.5 million, but four years later, in 1990 (the 5th year of the Bubble), it had swelled to over 10 million people. Particularly in Europe, Japanese tourists became second only to American tourists - and women in particular displayed a huge economic influence. Japanese women began to buy huge numbers of expensive luxury goods in Europe - one woman was reported to have bought an entire jewellery shop while travelling in Italy, while stores such as Gucci, Versace, Burberry, and even Harrods saw long queues of well-dressed Japanese women. Japanese tourists were especially shopping in huge numbers for Louis Vuitton and Gucci handbags, Savile Row and Armani suits (which new hirees often bought with their first paycheck) and the finest wines. All of these things made Japan an extremely rich and prosperous nation in the mid-to-late 1980s and early 1990s, with both GDP and GDP per capita soaring to among the highest in the world, and becoming the world’s first and only “luxury mass market”.

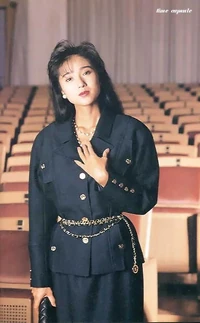

During the Bubble, Japanese companies, suddenly with a large amount of money to spend, were known to give generous budgets to the uniforms of female employees, representing at that point the fact a then-unprecedented number of women had entered the workforce. In 1985, just as the Bubble began, Japan introduced the “Equal Employment Opportunity Law” (EEOL), which brought significant public and social visibility to working women and to their aspirations for professional careers. In the wake of the law, women assumed a much greater responsibility at work, and the balance of power between the sexes began to dramatically shift. With a new-found confidence in both the booming economy and workplace gender equality, the traditionally submissive Japanese workplace woman rapidly gave way to a highly assertive, opinionated, confident, bold, “executive” kind of woman - a new breed of female executive who could party almost as hard as her male colleagues had begun to do. Suddenly, Japanese women now had an extremely strong self-assertion, and were more likely to ignore the opinions of men and do what they wished. This “strong woman” figure became a trope in numerous manga at the time. In some estimates, 1/3 of women in the workforce worked as an “Office Lady” or “OL” (オーエル) for short. The OL was usually a young woman, usually around 20-25, who kept care of her appearance, performed secretarial and clerical work (this included cleaning the desks, answering telephones, making tea and greeting clients), and was obedient to her male colleagues. They were by intention meant to represent a beautiful image in order to represent the office, and so were often called an “Office Flower” at the time. Combining with the image-obsessed general feeling of the Bubble period, as well as the boom of the Japanese city of Kobe as a hub of fashionable, wealthy young women (in a style called the New-Tora[1]) a strong desire for luxury, sexy, daring and flashy fashion grew amongst Japanese women. Ironically, despite an increasing social progress of feminism, Japan had entered an era in which women were trying to regain their sensual femininity. Additionally, by the 1980s, young women in their 20s had the largest amount of disposable income of any segment of the Japanese population, and as seen by the “City Pop” aesthetic of the early 1980s, had a desire to spend extravagantly. This was only boosted by the “Bubble Economy”, as the Bubble’s strong sense of optimism, enhanced by the idea of Nihonjiron (日本人論) - widespread beliefs at the time that Japan’s case of economic growth was “thoroughly different to other countries” and that Japan was “different to other countries”- meaning that people believed that land prices especially would continue to rise forever after World War II. This even lead to the word recession being called the “R-word” during the Bubble, as the idea of recession in Japan became simply unthinkable. These kind of ideas provided young women with a strong confidence in their ability to find work upon graduation and in their future prospects in general, and led a lifestyle of pleasure and play.

The Bodikon style as we know it today, while a nationwide phenomenon, first emerged in the city of Osaka in late 1985 and early 1986, arriving in Tokyo and other Japanese cities in October and November of 1985. The general style was an immediate craze amongst young women, especially the OL, and by mid-1986 had become mainstream fashion in Japan - being worn on the street, by OL at work, at formal events, and even (secretly) at school. High school and college students were known to imitate the Bodikon style and the associated “Wanren” hairstyle (discussed later on this page).

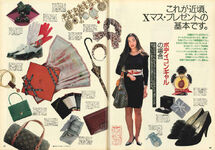

A key selling point of the Bodikon style was its sexy appeal, enhanced by its brash sexual style of flattering lines to the body (hence why Bodikon stood for “Body Conscious”) and usage of neon, colourful designs- involving usage of neon colours of red, purple, pink or yellow, often primary colours. This followed a general neon trend in 1980s fashion. Additionally, “DC” (an abbreviation for “Designer” and “Character”) brands began to take off from the early 1980s, and their youth-led, Shibuya-based stores began to sell Bodikon clothes from late 1985 onwards, marketed towards the young and affluent workforce that post-war Japan had produced. These affordably priced clothes began to permeate throughout the country and became a cultural staple of how the Japanese perceive the cultural impact of the Bubble Economy. There were also influences of 1950s revival, apparent in the glamorous hairstyles popular amongst Japanese women and usage of furs in coats, bags, and accessories. This was most likely caused by the re-airing of popular 1950s movies such as “Kimi No Na Wa” (Your Name, 1953) by the Japanese public broadcaster, NHK, in 1985 and 1986.

It is impossible to talk about Bodikon’s history without mentioning the influence of the Japanese nightlife scene of the same period. The Bubble Economy, as previously mentioned, resulted in a “spending boom” by the Japanese- and this was especially reflected in nightlife. At the time, going to the discothéque was popular in Japan, and during the Bubble a plethora of new discothéques opened. These discothéques were high-end, having a “luxurious” feel, and often requiring a dress code for both men and women. The staff would all wear tuxedos and the male customers wore suits. Female customers tended to turn up in Bodikon outfits, but anyone who disrupted the classy atmosphere of these discos was not allowed in. At the time, nightlife was a status symbol and to go to such popular and expensive discothéques was highly fashionable. In Tokyo alone, there were several “nightlife areas” that exploded in popularity - these included Roppongi (arguably the most famous district), Azabu, Aoyama, Shinjuku, Shibaura and Tamachi (the last two started to become increasingly popular in the late 1980s after they had been redeveloped and had large open areas of land left). Even though teenagers were initially excluded from the nightlife in the Roppongi and Azabu areas of Tokyo, whom aimed their nightlife at “classy” working adults, teenagers and students hungry for nightlife would illegally gather in many discos across Tokyo, with teenage girls often caught wearing Bodikon fashion there. These incidences sparked a craze for Bodikon in the teenage girl demographic, but also raised concerns from traditionalists who claimed Japan was losing its sense of morality to the crazes of money and decadence. Famous discothéques of the period included the Maharaja (マハラジ) chain of discothéques, the Juliana’s Tokyo (ジュリアナ東京) discothéque (in the early 1990s, and arguably the most famous and influential discothéque of the time. This disco is mentioned later on this page), and the King & Queen chain of discothéques. Others, among manym included the Turia discothéque in Roppongi, Akasaka’s Ronde Club in 1994 (infamous for its extreme style), and Shibaura’s GOLD discothéque (which operated from 1989 to 1995).

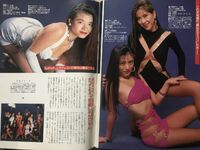

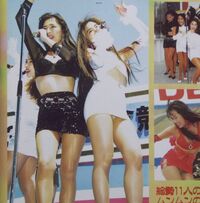

At the time, discos like the Maharaja chain and later Juliana’s (in the early 1990s) were central meeting areas for those women participating the now-mainstream style. They became places for young women, often teenagers between ages 15-19, and college age girls (early-to-mid 20s), to let down their hair and have fun. Frustrated by Japan's male-dominated society, Bodikon women were often seeking self-expression, flaunting their sexuality after spending day after day working as OL intended to be obedient and subservient to male colleagues. The Bodikon was regarded as “ a new breed of woman”- independent and uninhibited, proud of her body, and assured in her sexuality. This resulted in two forms of the Bodikon fashion - a “daytime variant” of 1980s-style, neon designer power suits as well as more conservative bodycon dresses intended for the workplace and for wearing on the street, and a “nightlife variant” of the fashion that was a lot more revealing and sometimes had “barely-there” clothing (described later on this page). “Wide shows” (ワイドショー), a then-emerging form of Late Night TV show that was a mixture of a news show, variety show, and a talk show, with an emphasis on 24-hour live coverage, young female presenters and sensationalist gossip, first emerged at the beginning of the Bubble in the mid-1980s, and these “wide shows” (such as the highly famous “Tonight” (トゥナイト) variety show that ran from 1980 to 1994) often ran late-night TV specials that followed the Bodikon “gals” to discos such as the Maharaja, Juliana’s, and also places like Shibaura’s “GOLD” discothéque, interviewing them and videoing them sexily dancing and gyrating on raised catwalk platforms known as the the otachidai (お立ち台)- a kind of platform in the discos satirically named after the palace platform where the Japanese Imperial Family would appear, reflecting how the Bubble customer was expected to be treated like royalty, often driving male crowds crazy with their overtly-sexual dance moves. The otachidai first emerged from the “Gize” discothéque on the 3rd floor of the Roppongi Square Building, a building that housed prominent discos on virtually all of its floors, before emerging in the Maharaja’s Azajuban branch and then becoming a nationwide phenomenon, emerging at Juliana’s Tokyo at its opening in 1991. These Juliana’s TV specials, as well as the Juliana’s own “Juliana’s Live” show from December 1992 onwards that would air weekly to millions of Japanese (even being sponsored by Coca-Cola), sporting presenters such as the then-extremely popular American rapper MC Hammer, often had TV cameramen crouched below the otachidais in order to peep and film at the barely-covered underwear of the Bodikon women dancing - but most Bodikon women seemed to like the public exposure, viewing it as a liberation of their femininity. Additionally, there was another notable late-night TV show that was influential on the style - “Gilgamesh Night” (ギルガメッシュないと / ギルガメッシュ・ナイト). It was a softcore, late-night TV show that featured the most influential Bodikon women of the day - especially featuring the prominent Ai Iijima (who is discussed later on this page). Although aimed at a male consumer base, Gilgamesh Night actually mainly attracted a female audience intent on looking like their Bodikon idols. VHS Tapes of Bodikon women and their dance moves were also popular sources of inspiration, and during the peak of the boom in 1993 sold incredibly well. The late-night TV “specials” and the “Juliana’s Live” late-night TV show, alongside the Techno CD albums which Juliana’s Tokyo released (as the first disco to mix session CDs in six volumes) became gigantic cultural staples all across Japan - released in volumes from 1992 to 1994, they sold like crazy, having sales of 1 million copies and being a large part of the disco’s profit since the disco itself wasn’t very profitable as a business model despite the huge visitor numbers of up to 5,000 a night during its peak. They also came with a free ticket to Juliana’s, resulting in many people attempting to flood into Juliana’s using their album tickets.

The cultural impact of discos like Juliana’s Tokyo during the Bubble period was phenomenal. Juliana’s in particular was a major social phenomenon - with people rushing from all over Japan, even from as far away as Kyushu and Hokkaido, to dance there. The Opening night (15th May, 1991) was reported as “pandemonium”, with lines going on for entire streets and so much frenzy inside that they had to stop the music. Dozens of high school girls would watch the Juliana’s Tokyo dancers, almost all wearing Bodikon fashion, on the previously mentioned late-night “Wide shows” on TV and attempting to emulate their dancing and style. Female elementary, junior high and high school students were notoriously known to use their sofas as “mini otachidais” while the TV displayed the Juliana’s Live TV Specials, and they would shake their “Juli fans” while dressed in Bodikon, all over the country, especially on Halloween. These young girls attempting to be Bodikon women would end up forming the basis for Kogal later on. Huge lines would form on the way from the adjacent Tamachi station to the Juliana's disco - the queues seemed to go on forever at the peak of the boom. One woman who had travelled all the way from Okayama to dance in Juliana’s told The Japan Times in May 1991: “I’ve been lining up for more than 50 minutes [to enter the discothéque]”, while another woman who had travelled from Hiroshima stated “I came to Tokyo [just] to dance here.” It was even said by people that “Juliana's Tokyo is probably the only disco that the Imperial Family are visiting in the early hours of weekdays”. As a major cultural sensation, these discos promoted the Bodikon fashions that were widely worn amongst Japanese young women of the time on a large scale, however the women who wore the more extreme “nightlife variant” of the Bodikon fashion were never more than a small minority - and more of a subculture that became a symbol of Shibuya and Roppongi. For those who engaged in Bodikon however, it was much more than just the latest fashion. The body was adorned in order to be made into a “spectacle”, with an emphasis on "collective sensation". Being a Bodikon was a subcultural affiliation that determined many girls’ identities and self-hoods, and the idea of a subculture of fashion centred around women that would go onto to become the central focus of Gyaru, developed in Bodikon circles. These “Disco Queens” as they became referred to would after work meet their fellow Bodikon friends, go shopping for (often designer/luxury) clothes in Shibuya, particularly at Shibuya’s luxury “109” shopping mall, and change into their Bodikon clothing, famously in the train station bathrooms of Tamachi station - you could see scenes like this broadcast on Japanese national television at the time.

The “Juliana's Tokyo” discothéque was located in a former warehouse in Shibaura, a bayside area in southern Tokyo that was undergoing redevelopment at the time and was desirable in the early 1990s due to its large plots of empty space, a rare commodity in overcrowded Tokyo. Opened in May 1991 during the height of the Bubble Economy, at a cost of ¥1.5 billion, it was a joint venture by Wembly PLC, the largest leisure service group in the United Kingdom (hence Juliana’s nickname as a “British discothéque”) and Nishho Iwai Corp., a top Japanese trading company. Initially it was to be the flagship disco for a disco chain throughout Japan. The styling of the discothéque reflected its high-class, flagship status. Patrons first were checked at the door for age and dress (this dress code, previously mentioned in this article, being a very common feature of Bubble-era high-class discos), then they were let through the large fractured glass doors where they were greeted by six Japanese women dressed in miniskirts, bowing in unison. From there, the patron entered the large 1200 square meter dance floor. A chandelier made in California hung from the ceiling, which reflected the multicolored laser beams. A stage stood at the front of the room, and raised plexiglass platforms were placed periodically throughout the room where foreign professional dancers would take 15 minute turns dancing to the 26,000 watt sound system playing a variety of Techno, Rave, Eurobeat, and House music styles. Juliana's originally started out playing Italo House and Italo Disco and quickly followed popular trends to Hardcore techno, which became the disco’s signature music style. The collection of new Rave and House genres, as well as imported European dance music, became known amongst Japanese clubbers as “Juliana’s Techno” (ジュリテク), alternatively known as “Hyper Techno”. Note that there was a difference between “Eurobeat” and “Juliana’s Techno”/Hyper Techno, although both were danced to by Bodikon women; Eurobeat was characterised by its melodic, poppy sound while Juliana's techno was characterised by a gloomy oppressive rave sound that was perfectly suited for hardcore dancing. Up to 3000 people at a time could be on the dance-floor and the VIPs could also retreat to lounges. There is a different “sound” of music attributed to each year of the boom - for example, in 1992, Hardcore Techno was popular, but in 1993 a more melodic, oppressive form of techno as well as house music were popular. By 1994, Eurobeat music was more prevalent.

The Maharaja chain of discothéques was also hugely influential on the style, especially in the style’s earlier 1980s years. In the 1980s and 1990s, there were some 60 Maharaja discos in Japan, with flagship “Maharaja Gion” known as "the best disco in the East". It was here that the fan-waving trend popular in the aesthetic started, when maikos (young Geishas) would go to the local Gion branch of Maharaja carrying feathered fans. Bodikon fashion was encouraged to flourish at the Maharaja as it earned Bodikon women free admission on “Ladies’ Nights”. Increasingly from 1987 onwards, women would dance in synchronised dance routines called “Para-Para” or more often at this point a hyper-Techno form of it, later known as “TechPara”. Para-Para/TechPara first emerged from the 1985 song “Take On Me" by A-ha in the early days of the Bubble. People at Maharaja started to dance by fluttering their hands along with the lyrics of the song, and some people would match their dancing with eachother. This kind of dancing took off and spread to every disco in the Tokyo area. The staff at each disco started creating their own routines to songs, and customers went to discos so they could see the routines and learn them. TechPara was similar to Para-Para, being choreographed, synchronised dancing using the hands and arms. Maharaja as such was known for the “First Para-Para boom” (mid-to-late 1980s), while Juliana’s became associated with the “Second Para-Para boom” (Early 1990s). The First Para-Para boom flourished until a notorious incident in the recently-opened Turia discothéque in Roppongi on January 5th, 1988, when a falling light killed 3 people in the disco. After this, the first Para-Para dancing wave ended, and the more extreme second Para-Para boom began. Wearing their Bodikon fashion, women (especially in Juliana’s) would often dance a mixture of freestyle dancing (influenced by the rave scene in the West) and this new Para dancing, on the otachidai (previously mentioned above). The otachidai had a height of about 130 cm, and was installed on both sides of the dance hall. The sexy dancing on the Otachidai - the focal point of the disco - often drove male crowds crazy, which Bodikon women found pleasure in - savouring their sexuality and leaving men powerless against the powerful, desirable woman. The Japanese media covered this extravagant partying extensively - on average 20 TV Crews a day, alongside the late-night TV shows, newspaper reports, interviews and even overseas media coverage - angering Traditionalists in the ruling political party, the LDP. Juliana’s in particular was believed to “ruffle official feathers” in Japan - because some people believed that the women's appearance and behavior was immoral. The media would continue to give Juliana’s heavy air coverage regardless of what influential Traditionalists in the government felt, creating visiting Juliana’s into a major status symbol, and spurned on by the defeat of the LDP government in the 1993 election for the first time since 1955, created the impression of a “break” with the traditionally Japanese post-war norms.

Despite the burst of the Bubble Economy in early 1992, the Bodikon subculture continued to prevail. At the time, Japan was in a sense of complete denial about the economic burst and continued to party on as if nothing had happened - in fact it took until early 1993 for the Japanese government to admit the Bubble had burst. In 1992, Juliana’s continued to soar to rapid fame and the fashion began to grow more and more extreme. The year 1993 is generally considered to have been the “peak year” for the style - by then the Bodikon women were so numerous, the media coverage was so intense, and the excess was so extreme that nearly every aspect of Japanese popular culture was affected by Bodikon women - from the late-night TV specials airing every night that drews tens of millions of viewers to infinite references in manga to the weekly tabloids detailing black and white pictures of the latest pasty-wearing women on the otachidais to the fashions even older women were donning by this point. By this point, some of the crazier Juliana's fashion looked like a strip show. Girls were one step away from being completely naked, wearing pasties and string panties. Other parts of the country such as Nagoya and Kyoto were strongly inspired by the Juliana's boom and the discos with locations there such as King & Queen and Maharaja were even more extreme apparently, attempting to outdo the excess at Juliana’s - for just ¥100 (significantly cheaper than the Juliana’s fee), you could dance practically naked! This encouraged the development of a phenomenon called radicalisation - where the Bodikon fashion began to become very extreme.

At the time, there were many prominent celebrities that embraced Bodikon fashion, that entered the public eye. These “Bodikon celebrities” were often “sexy” tarento (タレント) - which are notable television personalities in Japan, especially appearing as panellists on variety shows. “Sexy” tarento would be highly popular in the early 1990s. Others included models, “gravure idols”, and AV stars (what is notable is that Bodikon women often had links to the AV industry in Japan). More on the Bodikon celebrities is seen further down on this page.

By mid-1993, the radicalisation of Bodikon style was getting beyond extreme - even in Juliana’s itself, which was markedly more modest compared to some of the other discos, and complaints were beginning to come in. Complaints from the neighbors included reports of rowdiness, girls changing into their Bodikon outfits in the alleys surrounding the disco, and in June 1993 a Tokyo magazine published photos (staged with professional models, the disco's management insisted) of nearly nude women dancing on the otachidai. An atmosphere of chaos was prevailing through the discos by this point - women saw dancing on the otachidai as a competition to compete for men and outdo each other, contributing to the rise of radical outfits to attract the most attention. People used to fight for a place on the otachidai - elbowing each other and get in each other's way on purpose, and girls would pull each other's hair and burn each other with their cigarettes. Other women whacked other women off the otachidai with their Juli fans - this is humorously depicted in Yoko Kamio’s Boys Over Flowers manga (Hana Yori Dango, 花より男子), which was released at the time of all this going on. Additionally, the “radical” Bodikon fashion was now including public exposure of panties, on a special of the late-night TV show “Gilgamesh Night”, a tarento stripped down in public in central Tokyo to her underwear, and famously sometime in late 1993, a woman took off all of her clothes in a frenzy on the otachidai in Juliana’s in an impromptu strip-tease, nearly causing a riot on the dance floor. The (iconic) black and white photos of the incident ended up in one of Japan’s weekly magazines and resulted in Juliana’s management being summoned by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department for a meeting in November 1993. A police official who attended the meeting said: “We gave instructions that the otachidai is not a preferable place for customers to dance,". According to Yoshinori Kasano, Juliana's chief business manager, the disco's management had also been thinking of imposing limits on the displays of flesh. In December 1993, Juliana's removed the otachidai and replaced it with a "crystal stage" on which professional dancers were to perform, and a dress code was instituted prohibiting excessively revealing clothes.

Resulting from these incidents and now the crackdown on “radical” Bodikon by Juliana’s, from late 1993 people got the wrong idea that you could see girls stripping there, and so more and more perverted people as well as an invasion of girls from the countryside keen to see what all the fuss was about, who were often less sophisticated dancers. Because of this, attendance quickly dropped from 5,000 at a night at the peak of the boom to just 250 a night by early 1994. Bodikon was increasingly assumed to be a fashion of strippers - this probably wasn’t helped by the fact that numerous women in the AV industry were prominent Bodikon women. Bodikon gals responded to the Juliana’s crackdown by frequenting even more extreme discos - these included “Ronde Club” in Akasaka, which became very popular at the end of 1993 and early 1994. Here, the most radical of Bodikon gals were to be found - an S&M theme was pronounced in the disco’s style, with whips used as dance accessories by the gals and women wore “O-Back” underwear, which exposed their buttocks. Other Juliana’s customers, disappointed by the loss of the disco as a status symbol, began frequenting other discos such as Maharaja and King&Queen, resulting in a new revival of Eurobeat music.

Battered by the lack of business, Juliana’s attempted to give out large numbers of discount tickets and tried to get more customers to come but they were unable to get influential customers such as celebrities and wealthy Tokyoites like before. Bad influence on the club accelerated and they were only able to attract customers who didn't want to spend much money, and so the quality of customers went down and down. As the Juliana’s crackdown continued, they were also criticised for branding women who weren’t that radical in dress-code as “radical” and therefore banning them. A notable example of this was Kumiko Araki, arguably one of the most famous of the Bodikon celebrities. She stated that she never danced in her underwear, however was branded “radical” and was banned from entering the disco; this meant that she was not allowed entry to Juliana’s closing night in August 1994. In early 1994, Juliana’s announced it was to close at the end of August 1994 - in order to prevent the legendary name of Juliana’s Tokyo being “tainted” by recent occurrences.

By mid-1994, Bodikon however was still flourishing; it was still the mainstream style of most Japanese young women and its aesthetic was now being made lucrative into other industries; Takara Tomy for example even released a doll in 1994 based around the Juliana’s concept, for young girls who wanted to emulate the glamour of the women depicted on TV. By 1994, Bodikon had also begun to receive new foreign media coverage; this included a French documentary on the lives of Bodikon women, and a November 1994 Vogue article dedicated to the “bad girls” of today’s Japan. The style began to rapidly radicalise as 1994 went on, with pieces of daring and outrageous clothing being worn - such as chokers, PVC clothing and a heavy inspiration from anime characters such as Sailor Moon.

A variety of reasons can be also attributed to Bodikon’s decline, all largely tied to the bursting of the Japanese Bubble Economy. These included the sudden loss of a large leisure income making luxury brands unaffordable, the decline of the optimism surrounding the Japanese economy, the closure of many clubs in the Roppongi area, as well as the decline of the company in the centralisation of Japanese life (as partying such as this was hugely based around company hours and often paid for by the company). The influence of Bodikon style can be seen in the mid-to-late 1990s styles of Gyaru, where the party-influenced culture and sexiness appeal is reflected. Additionally, many of the pioneers of Gyaru originally started out dancing in the Juliana’s discothéque, where lots of influence came from.

After Juliana’s Tokyo, the last major hold-out of the style and of “Bubble culture” in general, closed on August 31st, 1994, Bodikon quickly vanished. With no central meeting area for Bodikon women left by September 1994, there was little justification to continue gathering in Bodikon circles. Shortly after, on September 2nd, 1994, it was reported Japanese drug agents arrested the American-born president of Juliana’s Tokyo, Gary Wayne Callicott, and his girlfriend Michi Tsuchihashi for possession of $500 worth of illegal drugs, by coincidence on the same day the disco closed. With the name of Juliana’s already placed in bad press throughout 1994, suddenly there was now another bad association with Juliana’s and by extension Bodikon culture. In late 1994, Bodikon diverged into differing “Gal” styles - forming the birth of today’s Gyaru. The younger Bodikon women, mostly teenage girls trying to emulate the sexiness and sophistication of Bodikon culture were now by this point taking on a more “schoolgirl” aesthetic, encouraged to rebel by the growing moral panic in post-bubble Japan over enjō-kōsai (compensated dating) and schoolgirl sexuality - a symbol of the materialistic decay Japan’s national character seemed to have experienced. As such, while it had been socially acceptable to be a schoolgirl wearing Bodikon, dancing on an otachidai in the early 1990s, now that Juliana’s had closed the Japanese moral consciousness was beginning to recognise the Bubble was over - and with it came a “sobering” of morality. These younger Bodikon women and their growing interest in portraying themselves as “rebellious schoolgirls”, defying the moral panic and merging the adult-like nature of Bodikon women with the portrayed innocence of schoolgirls would end up forming the first post-Bodikon Gal style, Kogal. Other Bodikon women, especially those women who were the “Radical” Bodikon gyaru, were more interested in the values of extreme tanning that had developed in the culture around 1993-1994. With the Okinawan-born singer Namie Amuro receiving a lot of attention by late 1994 for her distinctive tan, it seemed that tanning was still trendy and popular. As such, radical Bodikon women continued to “radicalise” in their look after 1994, eventually getting to the point where by the mid-to-late 1990s it was so incredibly extreme it had formed its own Gal style, called Ganguro. Other Bodikon women, especially the older women who had emerged during the mid-to-late 1980s, were reaching their Japanese “marriage age” or generally becoming middle aged by the end of 1994. As such, encouraged by the “employment ice age” that had emerged by this point post-Bubble, many simply left their OL jobs and became housewives. The style however continued to survive in a (gradually getting smaller and smaller) number - evidence for this visibly exists in the late 1994 and early 1995 volumes of “Heaven’s Door”, where Bodikon women and Tokyo’s disco culture are evidently portrayed. In December 1994, a “successor club” to Juliana’s, Velfarre, opened, led by the same DJ as Juliana’s, DJ John Robinson. At first, Bodikon women seemed to dominate the club, however by March 1995 - when the last Heaven’s Door volume was published - it was evident the culture was on its way out, if not had already made its exit; this was seen by Velfarre playing much more Trance music, a symbol of the growing mid-1990s Gal movement, instead of the more Bodikon-associated Techno (avex trax in the mid-1990s invested its money in Trance music and House music instead of Techno). By early 1995, when the Japanese public was left shocked by the lack of government action and widespread destruction during the Great Hanshin Earthquake in Kobe (the city’s infrastructure had been promised during the Bubble to be “Earthquake resistant”), as well as the terrorism of doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo terrorising the nation in the Tokyo Subway attacks, it was clear the mental image of the Bubble had been shattered, and with it, the culture of decadence and excess. By the mid-1990s, Bodikon were described as an “isolated tribe”, surviving in very small circles, and in 1995 the term “Juliana” was mentioned to be “dead”, with the term “Bodikon” gaining a more sexually-related meaning. However, in a 2002 article, there is mention of “Bodikon style” - whether this was a later Gyaru style that simply adopted the term or a small continuation of Bodikon disco culture however is left a mystery.

Fashion[]

Makeup[]

Make-up included a light foundation, either a scarlet/dark red lipstick or a pink lipstick, and purple and blue eyeshadows in a single colour without any gradation. Designer lipsticks, such as a Gucci lipstick or especially a Dior pink lipstick, were very popular for this look. Eyeliner was black and clear, and there was heavy usage of mascara. Blush was diagonal and was orange, brown, or yellow. Bodikon women also had relatively thick (and slightly bushy) eyebrows - it was mainstream to draw them much thicker than your own eyebrows. What was often done was drawing thick and dark straight eyebrows from the inside of the eyebrow to the end of the eyebrow using eye shadow, which couldn’t be as easily done with an eye pencil. Grey and dark brown eyebrow pencils were preferred for eyebrows around this time regardless of hair colour. After the Bubble burst, by the mid-1990s most women had very thin eyebrows - this process sped up when Tony Tanaka, a makeup artist, taught Japanese women the concept of trimming. In the Bubble period, women also had a strong self-assertion, so it was said that it was better to have flashy make-up - it was not possible to easily look fashionable with a more “natural” make-up.

Some Make-Up tutorials to help you out!!

-> https://youtu.be/jcA8b4L6T1g (This one has English subtitles, and is probably the most useful one. However it doesn’t cover everything that a Bodikon woman would have for her make-up).

-> https://youtu.be/18Cx6C1yD8c (This one has no commentary, but is a real, authentic make-up video from 1990 and therefore may be useful for getting the look just right!)

Hair[]

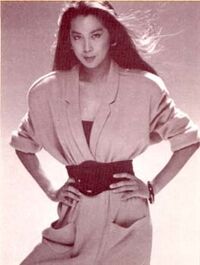

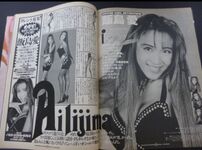

Hairstyles, regardless of type, were generally always long, often reaching the woman’s knees or chest. At least 60% of women in their twenties kept their hair longer than their hip area by the early 1990s.The hairstyle that most Bodikon women wore by far throughout the Bubble was the “One-Length” or “Wanren” hairstyle (Wanren, ワンレンボブ). This was where the hair was cut all in one length to create a mature, professional look, and was (extremely) straight and long. This hairstyle was popularised by idols such as Chisato Moritaka, and directly contrasted the “Seiko-chan” look of the early 1980s (popularised by Seiko Matsuda). The “Wanren” hairstyle was often paired with bodycon dresses or a power suit to form the “Wanren Bodikon” (ワンレン・ボディコン) set - this “set” was a crucial look in the Bodikon style and is often one of the most famous mental images of the Bubble Economy to many Japanese people. The Wanren Bodikon set attracted a lot of attention from onlookers during the time. Wanren hairstyles were often paired with a type of bangs known as “Tosakamaegami” (とさか前髪) bangs - literally “rooster hair” in Japanese - that could either be straight or curled, and sat at the top of the head. These bangs were upright “like chicken combs”, with the bangs slightly hung down and sprayed to keep them in place. As with any fashion that originated in the 1980s, hairspray was a Bodikon girl’s must-have and many women wrapped their bangs in curlers, slept, and then the next morning, used a hairspray to keep the bangs in place before going out. Wanren hairstyles didn’t always have Tosakamaegami bangs, but it was very common. However in the early 1990s during Bodikon’s final years the Wanren hairstyle did soften and Tosakamaegami bangs started to be worn with the Wanren hair less and less. This kind of look can be seen on Makino Tsukushi in the early 1990s volumes of Yoko Kamio’s Boys Over Flowers manga (Hana Yori Dango, 花より男子). Another type of popular Bodikon hairstyle was the “Sauvage/Sovereign hairstyle” (ワンレンソバージュ). With Sauvage meaning “wild” in French, this was a natural wave perm hairstyle with fine waves throughout the hair and lots of volume. This hairstyle was extremely popular in the mid-to-late 1980s and can basically be described as a Wanren hairstyle that was curlier. As Bodikon fashion’s heyday years were before the “Chapatsu boom” (茶髪/ちゃぱ) of the mid-1990s (when dyed brown hair, nicknamed “Tea Hair” due to its colour, went mainstream), most Bodikon women had black hair. However during the radicalisation of Bodikon around 1993-1994 (when Bodikon fashion started to become its most extreme and begin to resemble Gyaru), dyed shades of brown and even blonde hair became notable amongst Bodikon women, including famous AV idol Ai Ijima.

Clothing[]

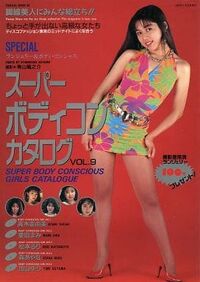

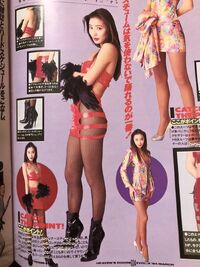

With regards to clothing, the iconic Bodycon dress was extremely popular. It was generally considered the signature clothing piece of the style. It was almost always a neon or a generally colourful colour (the most popular colours were red or yellow) and was a mini dress that emphasized the lines of the body, capturing the femininity of the body. The Bodycon dresses of the Bubble period were characterised by being flashy and conspicuous, and the neon colours of the bodycon stood out even in central Tokyo at night. The more highly exposed bodycon dresses attracted a lot of attention from men. Encouraged by the “fitness craze” that was ongoing in 1980s Japan, young women dieted in order to wear bodycon and kept a sharp body. Bodikon women also had a high level of confidence in themselves by wearing bodycon. Bodycon dresses at the time were characterised by their clear appearance of cleavage, waist, and hip lines. The chest was often “wide open”, as women were encouraged during the Bubble to expose their cleavage, and the length of the skirt along the hip line was up to the thighs. It was initially only worn in discothéques and disco halls, before then being popularised as fashion wearable on the street by around December of 1985. Many Bodycon dresses at the time were sleeveless, and so there were a variety of bras worn by Bodikon women. Some women wore strapless bras, and some even wrapped bras with “bleached” colours to make the shape of the bust look good. Colours and patterns of bodycon dresses varied, but the most popular was a vivid bright red that matched the colour of the lips with the colour of the bodycon. In addition, there were many flashy colours such as yellow, pink, and purple, and by the early 1990s it was common to see women wearing “wild pattern bodycon”, such as leopard prints and zebra patterns. Sequin bodycon dresses were very popular, with blue sequins being especially popular. Women wore Bodycon dresses for a number of reasons; these included attracting rich men, not caring about men’s opinions at all and going all out crazy, or feeling confident and self-assertive in clothes that flattered their bodies.

With regards to shoes, they were almost always high heels, usually being black and décolleté in leather with medium heel for a classy look.

A modern Bodikon woman flaunts her “Juli fan” for the camera

Furs, feather boas and a lot of gold jewellery would be worn alongside Bodycon dresses, often with luxury bags (such as Louis Vuitton or Versace bags) and gold chains. Chunky gold jewellery was very common and would be worn all over the chest area of the Bodikon woman.

There were numerous styles of Bodycon dresses, including the “Sexy Bodycon” style of string-bikinis and transparent dresses popular in clubs but inappropriate to wear on the street, but the most popular style, particular for daytime usage, was the One-Line style (ワンレン・ボディコン), which was a little bit more conservative than today’s Western bodycon, but was intended to be a “mature” and “sophisticated” style with a closely-fitting dress, or a suit-set, that was usually in one bright colour and uniform enough to pass for office-wear. The One-Line style (or Wanren Bodikon in Japanese) was the type preferred for the daytime activities of Bodikon gals, and is also known as the Daytime Variant. The One-Line style included the meticulous usage of the “power suit”, often colourful and with shoulder pads. This was considered a status symbol of business success for women, a highly desirable attribute amidst the success of the Bubble Economy. Sometimes a picture pattern, such as a pattern of Tokyo’s neon lights, would be worn on a power suit, but it was not super common. Power suits were worn nearly everywhere in daily life, from job interviews to nightlife to housework.

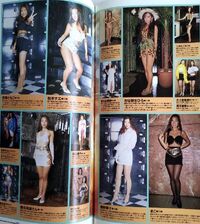

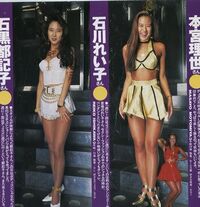

In this image from a December 1992 event in Juliana’s Tokyo, the difference between “Sexy Bodycon” (on the left) and the One-Line style (on the right) is clear. Bodikon women usually dressed in both.

A circle of Bodikon women at Avex Rave

“Sexy Bodycon” (also known as the Night-time Variant) became the prevailing Bodikon style by 1993 - with extreme style choices. Women wore neon-coloured string bikinis, transparent dresses as well as neon miniskirts, microbikinis and spandex, as well as extremely tight bodycon dresses with very short hemlines and often cut with revealing sections. By 1993-1994, neon-coloured PVC clothing, such as hot pink PVC miniskirts, were also highly popular in the disco scene. Pasties and string panties were often worn, sometimes even on the street. Women also wore large, customised belts and had long, often white gloves for a glamorous effect. Some of the more “radical” women - especially at Akasaka’s Ronde Club - even brought whips as dance accessories. Tanning was a major part of the radical look - along with dyed blonde and brown hair. The “Sexy Bodycon” look was popularised by influential celebrities in the Japanese media at the time - these include Ai Iijima, an AV idol who featured prominently on the late-night TV show “Gilgamesh Night” and was a mainstream celebrity in Japan - men wanted her and women tried desperately to copy her sexy antics. Additionally, there was also Natsuki Okamoto, a race girl, who helped to popularise this sexy version of the bodycon look, even adding her own touch to the style with the “high-leg” look, which was a bathing suit cut to reveal all the thigh and hip. By mid-1994, Bodikon women were also utilising chokers in their look, and inspirations for nightlife clothing borrowed from popular anime characters such as Sailor Moon in style.

Spandex miniskirts - a popular look in early 1994

Miniskirts were also popular, being usually paired with long stockings and gold chains, and were popular in both summer and winter.

Brands[]

Both “collection” (luxury) brands and the DC brands in the relatively easy-to-purchase price range became very popular from the mid-1980s onwards due to the demand in the student disco party and office scene. In particular, Pinky & Dianne was worn by so many people that it was called the "pin-die phenomenon." Famous DC brands included Alpha Cubic, Junko Shimada, MOGA, Zelda and Ingeborg (their 1980s and 1990s clothes can still be found for sale on online resellers like “Mercari”). Junko Shimada's colourful styles, particularly using colours like red and green, were “in-demand” for many young women of the time. Reflecting the new-found wealth of the Japanese, luxury goods and their brands were a key part of the aesthetic. At one point, any foreign brand was popular. Often, Japanese women would go to European countries and America, and sometimes Hong Kong if they were “poorer” (by Bubble Economy standards) to shop for luxury goods to wear. These included things from handbags, to necklaces, to even makeup, to the dresses themselves. In this period, showing off your luxury goods was a popular form of self-expression for many young women, and ownership of things like a Louis Vuitton bag or a Hermès scarf became a “rite of passage” into the booming middle class at the time.

TIP ; For many outfits, you can simply use a simple bodycon dress or a power suit and it will work out fine! It doesn’t have to be ridiculously expensive!

Popular Brands:

- Alpha Cubic

- Junko Shimada

- Pinky & Dianne

- Azzedine Alaïa

- Louis Vuitton

- Hervé Leger

- Hermès

- Burberry

- Harrods

- Gucci

- Dior

- Chanel

- Versace

- ”DC” brands (often these were independent stores and chains, popular examples include MOGA, Zelda, and Ingeborg)

Media[]

Some videos of Juliana’s Tokyo, the Avex Rave events, and “wide shows” that featured Bodikon women. These should give you a good impression of what Bodikon looked like on Japanese television at the time, as well as kind of impression of what the early 1990s Japanese nightlife scene looked like in general. More videos can be found using Japanese search terms (more linked below).

1.) https://youtu.be/kypqOXR1kHI

2.) https://youtu.be/-QhkTpmlfvM

3.) https://youtu.be/VSSTnGg4BW8

J-pop group Bed In and their modern Bodikon fashions

4.) https://youtu.be/bzY7J0Xle08

5.) https://youtu.be/dcb1wdAPVkc

6.) https://youtu.be/BaqTFl4Bxgs

7.) https://youtu.be/oXV0S48eVAk

8.) https://youtu.be/I3C3eNy7LK8

9.) https://youtu.be/VWQEU2LeW2w

10.) https://youtu.be/-lmKA1iqzUg

The typical Bodikon silhouette

Music[]

This is a YouTube playlist featuring many of the “hit” songs of the Bubble period, including many danced to in discothéques like Juliana’s, Maharaja, as well as some popular Japanese pop songs of the time. Many of the songs featured here had some of the earliest ParaPara (or TechPara) routines made. -> https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLQTUXyF6S2ICLT2vh7cXo2lQ-hHo6sD_b

Collection of the Juliana’s Tokyo albums, Maharaja Night albums, and other popular early 1990s Eurobeat albums such as the “Super Eurobeat” series was a “must-do” activity for any Bodikon woman of the period. Some links to a few of the albums are here below:

-> (Most) Juliana’s albums, excluding the Christmas album: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLEDLa9es_DYhtNqL5SVHu8orzrojfMf1Y

-> Maharaja Night albums are a little harder to find but are commonly found on YouTube.

-> Some of the “Super Eurobeat” series are available on YouTube, though are much more common as physical editions on online stores like Mercari.

Resources[]

MAGAZINES:

- HEAVEN’S DOOR (ヘブンズドア); Known as the “Bodikon equivalent to Egg magazine”, this magazine was published bimonthly in volumes from January 1994 to March 1995 and was a highly informative and detailed guide to Tokyo’s nightlife culture, focusing on the discos of Juliana’s Tokyo, Maharaja, King&Queen, Ronde Club, as well as the early opening months of Velfarre. Priced at ¥600 at the time, this magazine was a must-have for Bodikon women seeking to find the latest fashions and styles.

- The early volumes of Hanako magazine (1988-1994); launched in 1988, this was a lifestyle and fashion magazine aimed at young working women such as OLs, focusing on metropolitan Tokyo and the Kanto region around the city. Along with the latest Bodikon fashions, Hanako also focused on other aspects of Japan’s booming consumer culture during the Bubble, such as urban leisure, with a specific focus on international travel. It is still in publication today.

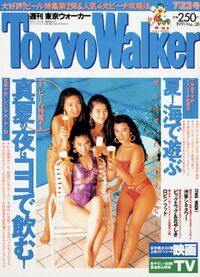

- The early volumes of TOKYO WALKER magazine (1990-1994): launched in 1990, TOKYO WALKER was a regional information magazine about the city of Tokyo that introduced high-profile events and information such as fine-dining and nightlife in Tokyo. At its circulation peak in 1993, over 80 million people in Japan were reading the magazine and it featured front covers of Bodikon celebrities such as Chisato Moritaka. The magazine would later decline due to the spread of the Internet and SNS, and stopped publishing in 2020.

-ZOKKON magazine: published in the period 1993-1994, this magazine specifically focused on the “radical” Bodikon women, with daring fashions and frequent appearances of “sexy” Bodikon idols, such as the Body-Conscious Girls idol group (B.C.G)

BOOKS: -Speed Tribes: Days and Nights with Japan’s Next Generation (1994) by Karl Taro Greenfeld - This is easily the best English-language source from at the time detailing Bodikon and the excess, disillusionment and decadence to be found among Tokyo’s urban youth during the early 1990s. This is a must-read for newcomers to this subculture.

-Platonic Sex by Ai Iijima - Autobiographical in nature, in this book AV idol, Tarento, and Bodikon celebrity Ai Iijima thoroughly explores her life, including a very heavily detailed section on the Bubble Economy, its hostess culture, the Bodikon disco culture of the time, and the early 1990s AV industry.

-Neo Body-Conscious Bible (1994) by Kumiko Araki - Written shortly before Juliana’s closed by arguably the most prominent of all Bodikon women at the time, this book provides an extremely good level of detail about the Bodikon culture.

-Gal Structure (1993, ギャルの構造) - Written at the peak of the otachidai boom in 1993, this book attempted to explain the mentality of Bodikon gyaru to older, more conservative Japanese who had a hard time understanding the decadence of the Bubble youth.

MOVIES:

-Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust - this humorous science-fiction movie sees a Japanese girl of 2007 travel back in time to the Bubble days of the year 1990, detailing the large differences that Japan underwent during the Heisei period (1989-2019). [